Family, Identity and Belonging: Photographer Fernanda Liberti’s Journey to Syria

© Fernanda Liberti

Earlier this year, I sat down with Fernanda Liberti to discuss her moving exhibition Dust From Home, a deeply personal exploration of identity, family, and belonging that emerged from her journey to rediscover her Syrian roots.

Inspired by her previous collaboration with indigenous leader Célia Tupinambá and catalysed by her experiences of isolation in London, where she previously resided, Fernanda turned her lens inward to explore the complex layers of her family's history.

Dust From Home illuminates the universal themes of belonging, the impact of migration on identity, and the power of art to bridge generational and geographical divides. What began as a family lunch in Brazil – bringing together relatives who hadn't spoken in a decade – led Fernanda to Syria, where she discovered dozens of relatives she never knew existed, an inspiring artistic community, and ultimately, a deeper understanding of herself.

Now that the exhibition has concluded, we reflect on this journey and its lasting impact on both her artistic practice and personal life.

© Fernanda Liberti

How did the process of conceiving this project come about, and what led you to explore your origins and past?

This project actually began in 2022, as I had been wanting to gain a deeper understanding of who I was, my family, and my history for some time. After spending four years alongside Célia Tupinambá for the project Dancing with the Tupinambá, I was profoundly inspired by her journey of reclaiming and recovering things that had been left behind, erased, or taken away. My research has always carried this interest – bringing to light what has been forgotten and needs to be remembered.

During the opening of our exhibition in Paris, I was already thinking about my next project when I felt a strong calling to tell my own story. In Brazil, there is something quite unique: people from anywhere in the world come here and, in some way, are integrated. However, in this process of integration, we often let go of parts of our identity to avoid being seen as immigrants or refugees – this was the case for my family. And in doing so, a lot was lost.

My great-grandparents passed away dreaming of taking their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren back to Syria, but they never had the means to return. So, I wanted to be the one to make that journey since no one else had. I had always been drawn to things connected to Syria, things I loved without even realising where they came from. This trip became a journey of self-discovery – understanding who I was, my family’s roots, and why we are the way we are.

Ten years ago, my grandmother passed away, and my family became divided in a major dispute. No one saw each other anymore, no one celebrated together. After moving to London and experiencing loneliness, it struck me that I did, in fact, have a family – we simply no longer spoke to one another, but they still existed. That was when I felt the calling to be the force that would bring my family back together.

I organised a lunch and invited all my relatives who hadn’t seen each other in a decade to photograph them. I had never photographed my own family before, and it was far more stressful than any campaign I have ever worked on (laughs). But that day was incredibly meaningful for all of us.

At that lunch, I started gathering information about Syria, piecing together this giant puzzle in which each person held a fragment. My family would tell me, “You can go, but you won’t find anyone from our family there.” Yet, when I arrived in Syria, I discovered that I had a huge family – over 50 relatives still living there and others spread across the diaspora.

© Fernanda Liberti

Do you think you would have embarked on this project if you had stayed in Brazil and hadn’t experienced loneliness in London?

I don’t think so. Many things wouldn’t have happened if I had stayed in Brazil. Both leaving and returning have always been powerful catalysts in my journey.

When you leave home, your identity is thrown into question. You start wondering, “Why do I feel alone?” Bringing my family together after ten years was a profound experience and also the starting point for this project.

It’s much easier to find a new family in the outside world than to mend the one you already have. Today, I have close ties with family members I never imagined I would. My family’s history is full of pain, loss, and resentment, and this project helped some of us look at our past with a new perspective – with kindness, with pride, with a sense of meaning. My dedication inspired my family, and that brought us closer. Each person held a piece of the puzzle, and in the process, I discovered other relatives who are also artists. That made me feel less alone.

What was it like to immerse yourself in your past? How has it influenced your present?

It changed everything. It changed who I am, the way I see the world, the way I navigate relationships. I have always been someone who gives a lot of myself, and that has often led to disappointment – until I realised that in Syria, everyone is like that!

Although I am deeply inspired and connected to Brazil, I always felt somewhat foreign, somewhat different. But when I arrived in Syria, I really felt at home. It was a powerful realisation – to recognise that so many things I loved and felt deeply drawn to came from there, without me even knowing it.

It was overwhelming to find myself in a place where I didn’t speak the language, a country that had been under dictatorship for over 50 years, without much electricity – and yet, to feel completely at home among people I had never met before.

During this experience, I led a workshop for Syrian artists in Damascus at Madad Art Foundation, and it was one of the most inspiring things I have ever done. I met young artists who had only ever known war – who grew up in conflict, whose entire artistic practice was shaped under dictatorship, where they could never fully express themselves. And they are some of the most incredible artists I have ever met.

Connecting with the local art scene was deeply enriching. The European art scene often feels like an echo chamber – repetitive, homogeneous. It’s difficult to stay inspired in that context. I feel that both life and artistic production often come from a place of comfort. But this experience in Syria pulled me out of that space and made me see art in a much more deep-rooted way.

© Fernanda Liberti

This project has an investigative element to it. How did you begin this journalistic process?

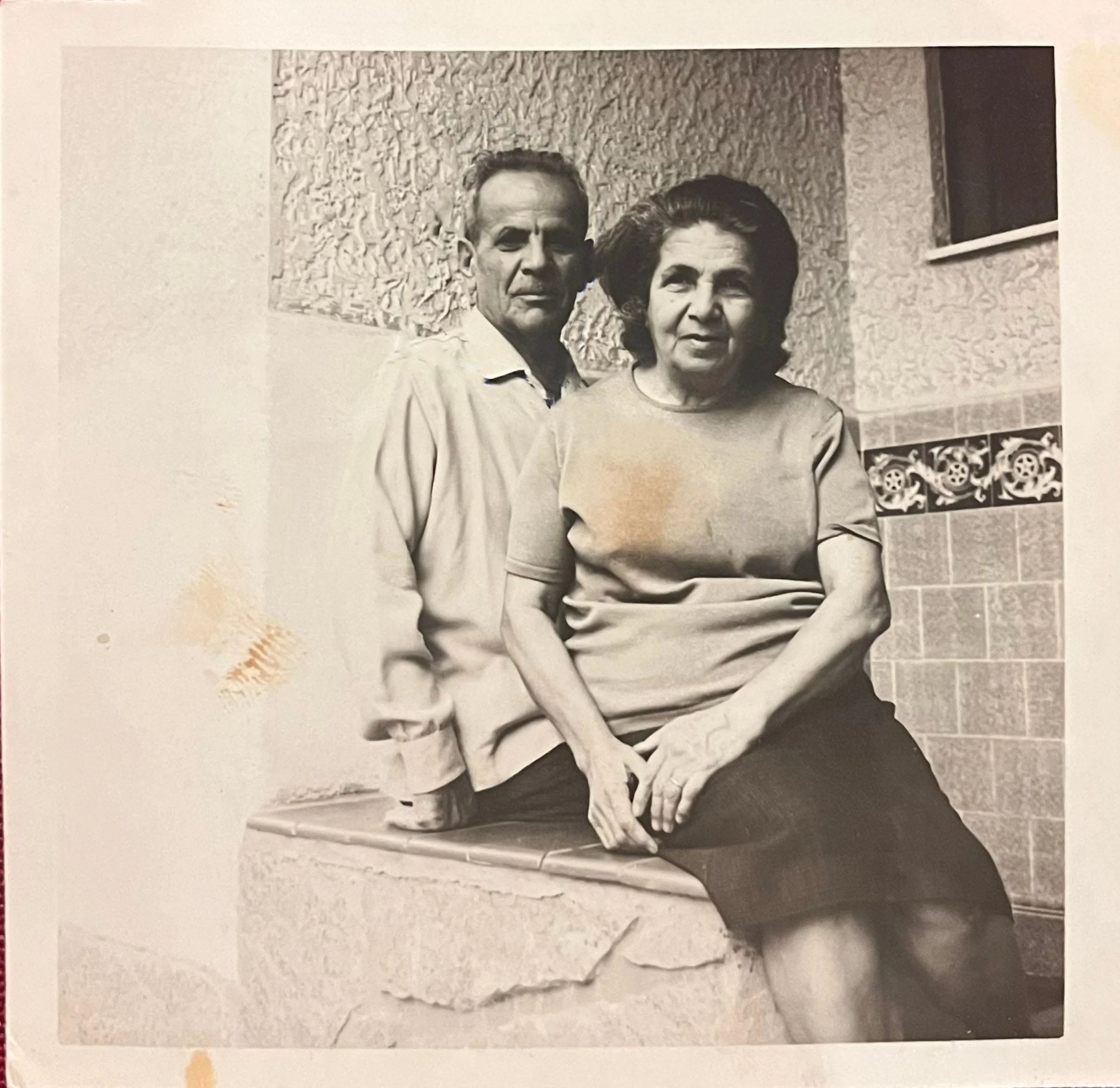

It all started with my great-aunt Regina. One Christmas, I invited myself to spend the holiday with her, and she began showing me old family photographs. That was the first step in what became a collective process of reclaiming our history. Over the next two years, I would receive phone calls from relatives sharing things they had found along the way. Unexpected characters emerged throughout the journey, and now I’m in the process of retelling this story to them.

The project had three phases:

Gathering the family archive in Brazil.

Investigating the places my family inhabited in Rio de Janeiro and how these places intersect with my own story.

Travelling to Syria.

I discovered that my great-grandfather owned a fabric shop in the Saara district of Rio de Janeiro and was one of the few people who could read and write in Arabic. He used to help fellow immigrants transcribe letters, and people would know if the news was good or bad by the amount of Arak (typical alcoholic drink) he would pour them.

That’s what I love about photography, it takes you places, connects you with people, opens doors. This process also brought me closer to my identity, I started learning Arabic. Everything is connected.

© Fernanda Liberti

Was there a moment in this journey that was particularly impactful?

Without a doubt, the day I found my family in Syria. I had always dreamt of having a big family – and then, suddenly, there they were.

What makes this story even more incredible is that it all began with my grandfather’s medal. A friend of mine in London connected me with Syrian artist Hrair Sarkissian who recognised it and told me he had the same one, which he had picked up in a famous Orthodox church in my family’s hometown the previous year. I decided to visit the city and get a new medal for my project. That alone would have been enough for me – I had no greater expectations.

When I arrived in my family’s city and went to the church, I searched the shop for the medal, but it wasn’t there. I asked some of the nuns, and after much persistence, one of them finally gave me one.

My guide suggested that I ask the nun about my family. That led us to another church, where a Venezuelan-Syrian priest pointed to a woman and said, “She is from your family.”

Within an hour, I was having lunch at my relatives’ house. It was completely unexpected. We had lost contact with this side of the family over 20 years ago. Syria has been at war for more than 12 years. I had no expectations whatsoever – yet somehow, everything fell into place.

© Fernanda Liberti

Tell me about the process of turning all this into images. Did you have a clear vision of how the project would unfold visually?

I didn’t know what the photos would look like, but that’s part of my process. It’s always a journey of discovery – I find the unknown far more exciting than the known. These explorations are essential to me, they are a fundamental part of my work. I never know how a project will end, and that’s precisely what interests me.

It was a complex but fulfilling process… It was the biggest space I had ever been given to exhibit my work, yet somehow, it still wasn’t big enough to contain my entire life story, my family’s history, all the emotions and exchanges, within a single photographic project. I spent two months in the editing process, but I had the support of my therapist and my artist friends – both Syrian and Brazilian – who helped me break everything down.

I enjoy editing. It’s a painful but rewarding process.

The editing process is crucial—it’s what defines the project. I imagine that, given the complexity of this one, it must have made things even more challenging. Did you ever feel limited by photography as a medium when trying to tell your story?

These days, our relationship with photography is much more direct because of smartphones – we spend the whole day looking at images. So, I think a lot about the visitor’s experience. How can I, to the best of my ability, convey some of the emotions of discovery that I felt throughout this journey? Through textures, scents, details, fabrics… What kind of experience will someone have when they see my work in person versus on a screen? I carefully considered everything – the scale, the choice of printing on different materials – all with the visitor in mind.

Syria is a place of stark contrasts, of beauty and destruction coexisting. It’s a land of dualities, and I wanted to bring that into the exhibition as well. I don’t think photography is limiting, I believe it can be expanded. More and more, I want to think of myself not just as a photographer but as a visual artist, with photography being just one of the mediums and materials I use to bring my ideas to life.

The exhibition process was incredibly rewarding. I brought elements from Syria into it – for example, the frames I used were handcrafted there, made in a workshop by artisans who paint them by hand all day long. Every ephemera came from antique shops. The entire process involved a great deal of walking, searching, collecting. There were elements of fashion, antiques, photography.

This is my story, but it isn’t about me. Many people see themselves in it because, at its core, it’s about family, about love, about finding oneself and understanding who you are. It goes back to the power of art to connect with each other, to recover buried relationships and to build new ones.

Also, my desire to go places on my own says a lot about what women can build for ourselves. Photography is still a male-dominated field, where men are free to go anywhere while we are often made to feel afraid. There are always people who try to impose limits on what we, as women, can do. But I also think it’s important to show that in these so-called dangerous places, people are living their lives. That’s what made me fall in love with photography – the possibility of showing different realities. At the same time, I was very conscious of not letting my story romanticise a conflict. That carries a weight of its own. The same country that gave me my family, is the same where countless others are looking for their missing relatives who were cowardly taken by the fallen regime.

© Fernanda Liberti

Finally, what did your family think of the final outcome?

It was incredibly emotional – for everyone, including me. To have ours and our ancestors' stories in a museum gives a redemption opportunity to a lot of pain. Even the process of constructing the installation of the Palmyra Museum, which had been partly destroyed, filled with my family’s memories, brought back something deeply personal. I remembered being 12 years old and pinning things to my bedroom wall. It was special to give my family’s story this space, this sense of importance.

I think immigrant histories are often marginalised. When someone from the Global South moves elsewhere, they are called immigrants, whereas Europeans and Americans are seen as expats. I am deeply proud of my family’s story – and, in a way, it mirrors my own. Today, I too am an immigrant. The difference is that I have the privilege of being able to return to my country.

Now, my plan is to take this exhibition to other places and see how the work takes shape in different spaces. And, of course, I plan to return to Syria this year. It will be fascinating to witness the country in a post-dictatorship era.